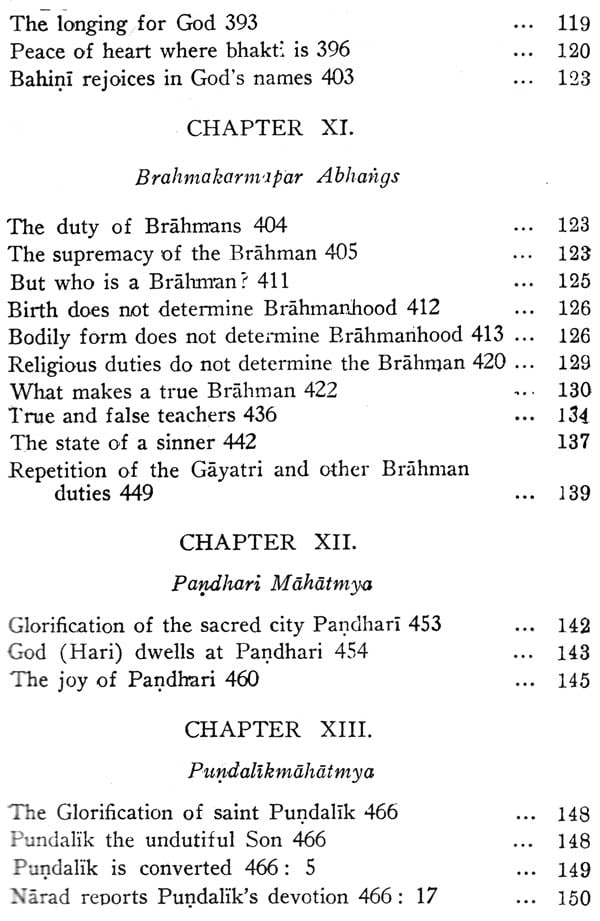

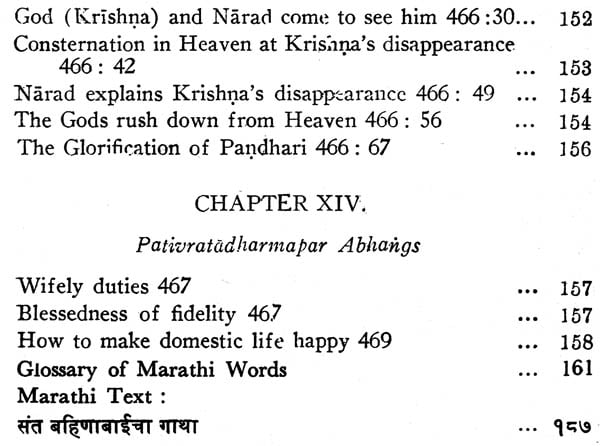

| Specifications |

| Publisher: MOTILAL BANARSIDASS PUBLISHERS PVT. LTD. | |

| Author Justin E. Abbott | |

| Language: ENGLISH AND HINDI | |

| Pages: 304 | |

| Cover: HARDCOVER | |

| 7.00 X 5.00 inch | |

| Weight 300 gm | |

| Edition: 1985 | |

| ISBN: 9788120813342 | |

| NAU132 |

| Delivery and Return Policies |

| Ships in 1-3 days | |

| Returns and Exchanges accepted within 7 days | |

| Free Delivery |

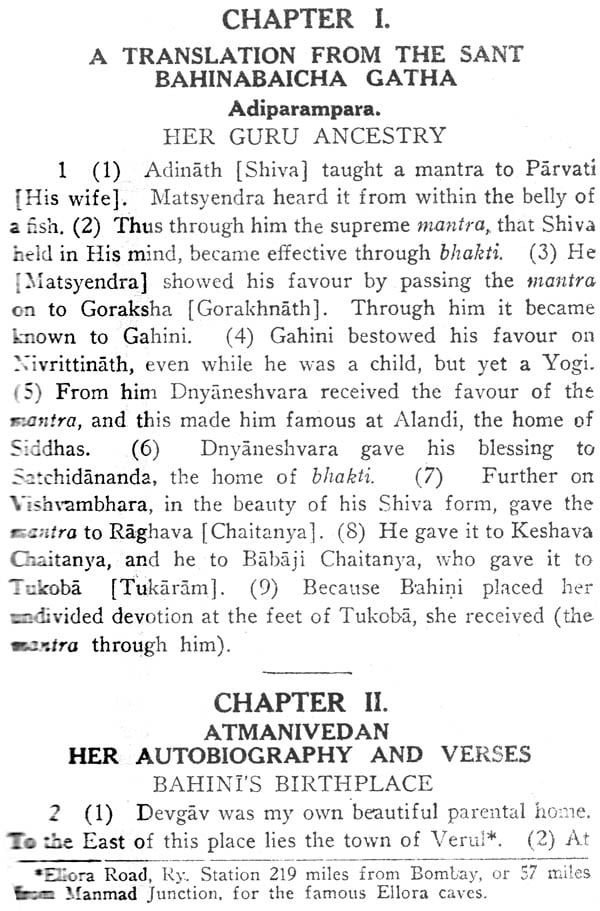

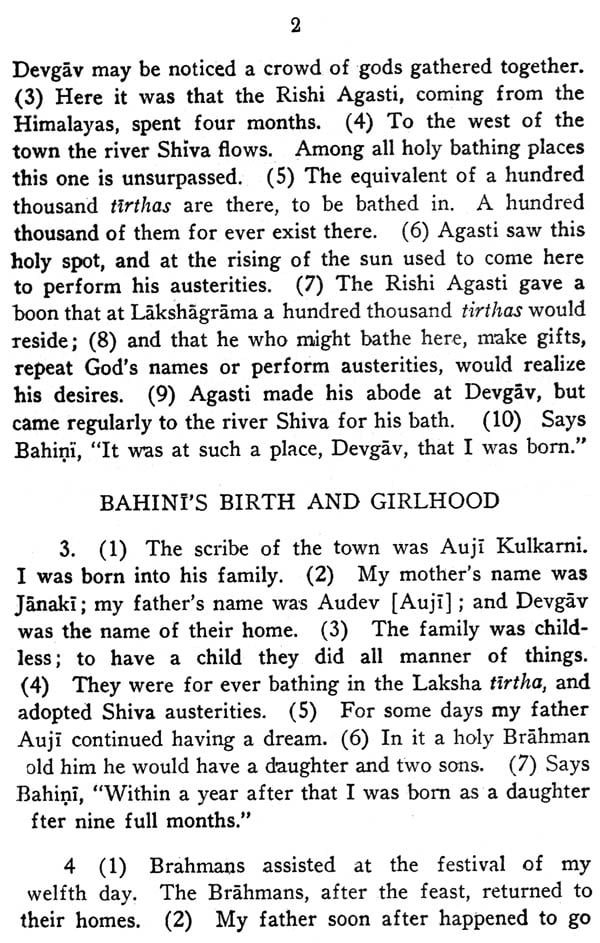

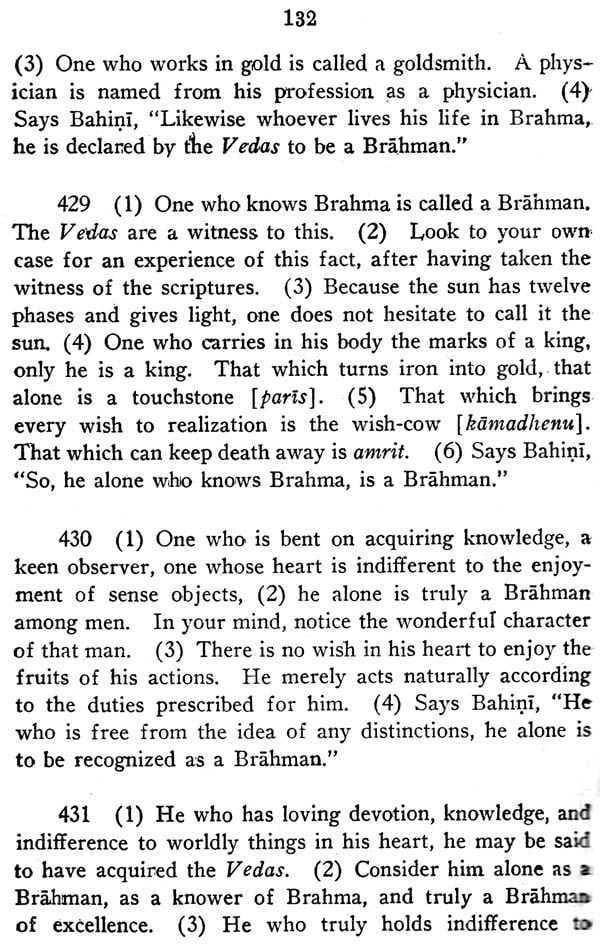

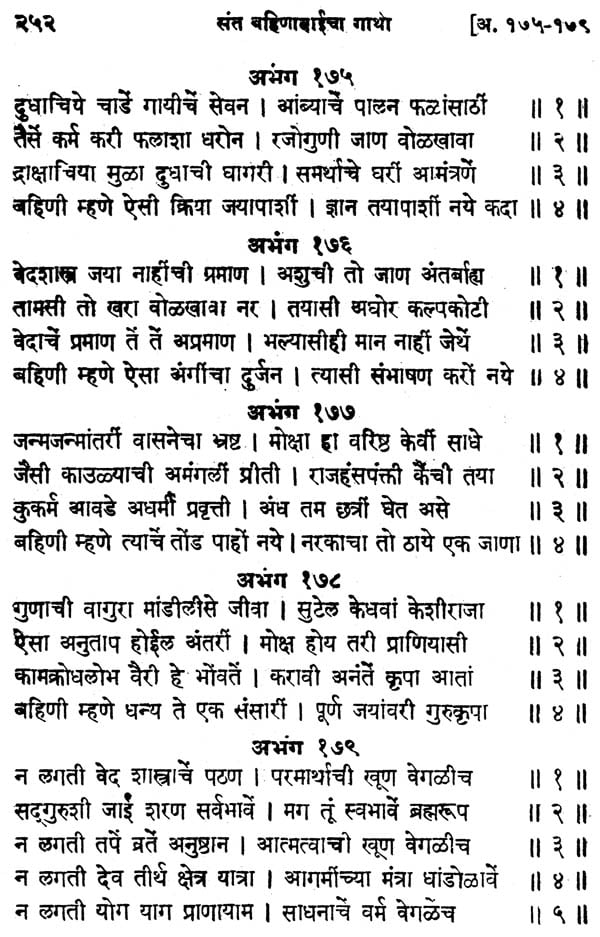

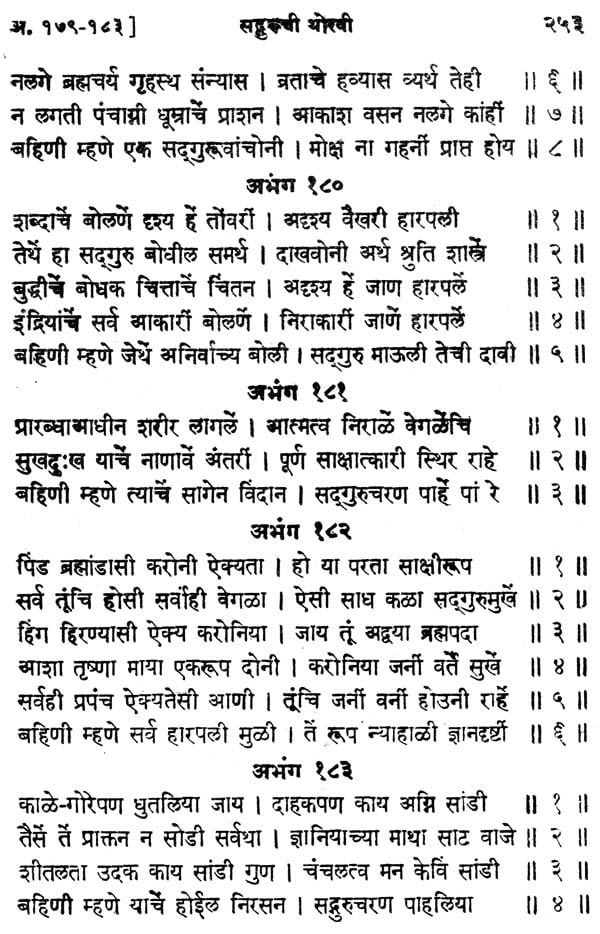

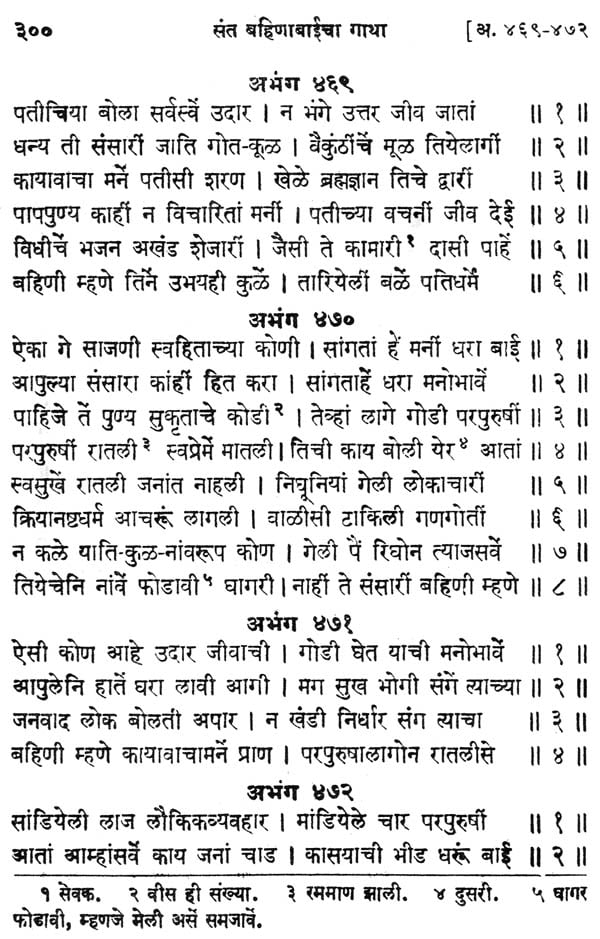

The Maratha people can point with pride to many of their poet-saints who were women of literary ability, wise in philosophy and godly in character. Bahina Bai is one of them. The present work introduces to English readers, to a larger circle of readers in India and to the West where the name was absolutely unknown but worthy of being known, this saint-poetess whose autobiography and verses have been known to but a few outside Maharashtra.

The author has not attempted to translate all the verses of Bahina Bai. Instead, he has chosen such portions as seemed best adapted to give to the English reader the thoughts of this Indian woman that found expression in her verses nearly three hundred years ago.

Bahina’s autobiography, unique in Marathi literature, supplies all that is known of her. But it covers only the details of her early years. For her later years with their mental struggles, temptations, perplexities ‘and thoughts of approaching death one has to gather from her verses such details as she has made possible.

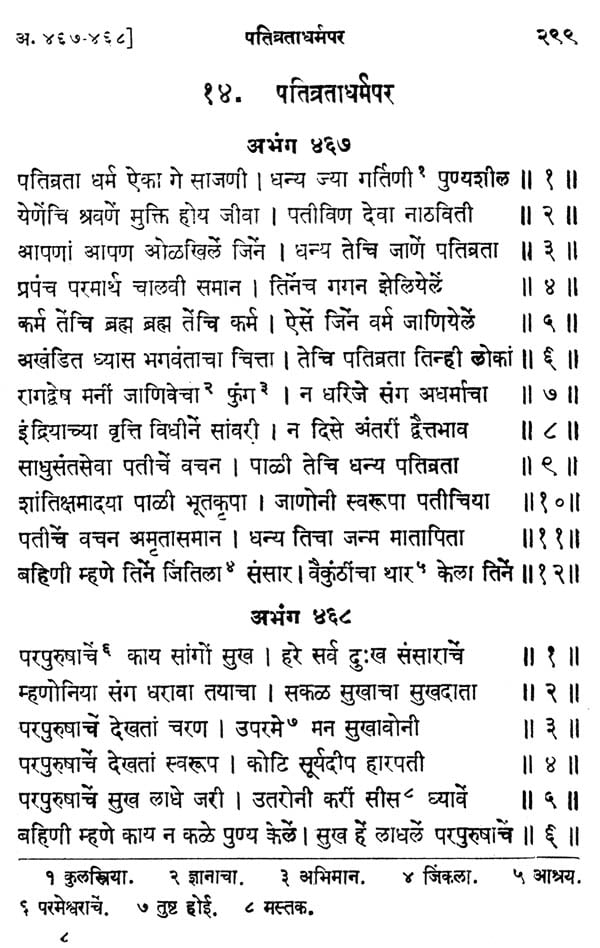

The writings of women are a rarity in Indian literature; this makes Abbott’s translations of Bahina Bai’s poems welcome from the outset. Moreover, the fact that a significant portion of Bahina Bai’s work is autobiographical makes the translations all the more valuable. For they provide readers of English with a Hindu wo- man’s own account of her experiences and aspirations, as well as her own interpretation of her tradition. Final!y, Bahina Bai’s parti- cular experiences, as well as her particular interpretation of her tradition, are important in themselves, for they document an important reconciliation of competing ideals in the Hindu tradi- tion.

Bahina Bai’s greatest significance is the reconciliation that she achieves between duty and devotion, dharma and bhakti, marriage and love of God.? Such a reconciliation is rare among the medieval Indian women saints whose writings or life stories are known to us: for Antal, Mahadevi, Lalla, Mira, and others, the love of God made impossible a stable married life. They rejected human sui- tors and husbands, and sometimes even dispensed with conven- tonal modesty; they thus dramatized their bhakti, but they failed to fulfil the dharma of a woman. Bahina’s autobiography (2-78), by contrast, though it reveals the conflict in her marriage between her God and her husband, also portrays a resolution of the con- fiict : in the end, Bahina is able to have both her marriage and her Lowe for God.

The series of Bahina’s poems describing her former lives indi- cates that this state of things is the culmination of a long progres- sion: in the first three of her twelve previous lives, she reports, she was not married (90-92); about the next four lives she implies, though she does not state clearly, that she was unmarried (93); in her eighth life, she says, she became a young widow, and, in the ninth, she died at the age of nine (94); whereas in her tenth, ele- venth, and twelfth lives (94-96), as well as in the life during which She is writing, she was a married woman devoted both to her God and to her husband.

The superiority of this combination is further indicated in the "Verses on Wifely Duties" which close the present volume. While some of the poems (468, 471, 472, and part of 470) praise a love of God which defies convention and overrides worldly concerns, others (most clearly, 469 and 473) prescribe dutiful wifeliness with- out referring to any god but the husband. But a few of the verses seem to indicate that, for a woman, marriage and devotion are necessary to each other. On the one hand, Bahina states, ‘""With- out a husband one does not keep God in mind" (467.2), and on the other hand, "she whose mind constantly contemplates God, She is recognized in the three worlds as the dutiful wife"’ (267.6).

In Bahina’s own life, the conflict between loving God and being a good wife is resolved somewhat arbitrarily—by chance, one might say, or by grace. Her husband stops Opposing her devo- tional life, and comes to share her love for God, but this occurs only after her husband has threatened to leave her, and she has chosen him over God ("My duty," she writes, "is to serve my husband, for he is God to me." 35.4). These events may seem uni- que, irreproducible in others’ lives, but Bahina Bai nevertheless provides an example for other Hindu women, a promise that they too can remain faithful to their wifely duties and still participate fully in the bhakti tradition. The writings and life of Bahina Bai thus contribute to what might be called the domestication of medieval bhakti, its reconciliation with the world and with the orthodox tradition.

I take special pleasure in introducing to English readers the Saint and Poetess, Bahina Bai, for, until recently, her autobiography and verses have been known to but a few. A few manuscript copies of her works exist. The first printed edition, edited by Dhondo V. Umarkhiane, appeared in 1914, and was soon out of print. Another edition, print- ed from another manuscript, edited by V. N. Kolharkar, was issued in 1926. It is probably true that there are not many Marathi readers of her poetry. To introduce Bahina Bai to a larger circle of readers in India, and to introduce to the West a name there absolutely unknown, but worthy of being known, I consider a privilege of no mean order.

I have not attempted to translate all her verses, for the translation of the whole, with the text, would make too bulky a volume. I have, therefore, chosen such portions as seemed best adapted to give to the English reader the thoughts of this Indian woman that found expression in her verses nearly three hundred years ago. smile to the Marathi reader. I acknowledge my debt there- fore to Pandit Narhar R. Godbole for information and suggestions that have enabled me to avoid many a pitfall. Copyists of Marathi manuscripts were not always careful copyists. There are differences, therefore, between the two printed texts mentioned above. 1 have in the main followed Kolharkar’s text, because it is now the only text available. I have gone into the question of the respective merits of these texts.

I may also add here that Bahina Bai’s verses require considerable ‘umination for the Western reader. Her allusions to Puranic stories, customs, to philosophic thought, to religious observances and the like, are outside the Westerner’s ken. But to make the necessaty explana- tions in notes and footnotes would take so much space and lead me so far afield, that I have limited myself to the most necessary explanations in footnotes and glossary, and have left it to the Western reader to gain further infor- mation as best as he can, if he feels an interest in doing so.

To the Rev. J. F. Edwards of Bombay, I owe a debt of gratitude for his assistance in seeing this volume through. the Press.

I do not hesitate to acknowledge many unusual diffi- culties in translating her language and thought. Her style is exceedingly elliptical. Her vocabulary and grammatical constructions, belonging to the Marathi of three hundred yeaTs ago, create many difficulties for me, a foreigner.

Send as free online greeting card

Visual Search