| Specifications |

| Publisher: Abhinav Publication | |

| Author: Swami Sivapriyananda | |

| Language: English | |

| Pages: 148 (Color Illus: 69, B & W Illus: 14, Figures: 9) | |

| Cover: Hardcover | |

| 9.8" X 7.5" | |

| Weight 630 gm | |

| Edition: 1990 | |

| ISBN: 8170172314 | |

| IDE056 |

| Delivery and Return Policies |

| Ships in 1-3 days | |

| Returns and Exchanges accepted within 7 days | |

| Free Delivery |

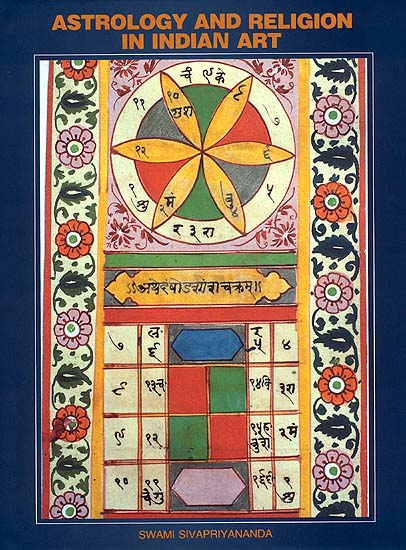

In India, astrology is not merely a method of divination, but an integral part of its religious and cultural traditions. The book explores the interrelatedness of astrology, art and religion. In the beginning it deals with the foundations of Hindu astrology and its rich symbolism. It then goes on to describe the various representations of astral symbols in the traditional arts of sculpture and painting. Finally, the book shows how artistic representations of astral deities such as planets and stars are used in ritual and worship.

The author, Swami Sivapriyananda, was born in 1939 into a royal family of a princely state in Gujarat. He studied Sanskrit and Pali at graduate and postgraduate levels at Pune University. He also studied for the traditional 'Kavya-tirtha' of the Bengal Sanskrit Association, Calcutta.

After this, he went to England for postgraduate study in Archaeology at the London University. He took sannyasa at Rishikesh in 1974 and since then has visited many ashramas, saints and centres of traditional learning in search of material on forgotten and neglected aspects of Indian religion and culture. At present, he is working on the philosophy of the Nathas and on the traditional of erotic mysticism in India.

THE astrologer understands abstract concepts of time, space and the nature of heavenly bodies in terms of mathematical symbols. But such symbols are difficult for the layman to understand. He needs them to be expressed in simple, everyday, images. Astrological art makes complex astrological and cosmological concepts easily understandable. It takes everyday images, such as human and animal forms, geometrical shapes (yantras) and colours, and turns them into symbols of astral events. And it does this in an aesthetically pleasing manner. The icons of planets and constellations, diagrams of planetary positions and decorative horoscopes that are common throughout Indian art history are all examples of astrological art. But astrological art is not a particular school or style of artistic tradition. It uses and covers all the styles and schools common to both classical and folk traditions to graphically represent astrological concepts.

The making of icons and symbolic images has another function as well. It is a form of magic. Many people believe that an image of a person or thing shares some of the qualities of the original. Many prehistoric, and even modern-day primitive tribes’ paintings depict birds, animals and abundant fertile fields as magical charms, believing that the birds and animals will be easily hunted and that the fields will yield rich harvests. The idea behind making images of planets and constellations was to summon the essence of the original and to attract their favourable influence. This idea was known all over the world. A 15th century Florentine philosopher and doctor called Marsilio Ficino (1498 A.D.) in his medical book called Libri di Vita (Book of Life) recommended the use of images of planets to attract their attention and to persuade them to be more favourable. In India, images, paintings, geometrical yantras, mythological stories about astral divinities were evolved with the same magical purpose in mind. The images were, and still are, made of special metals, given specific forms and objects to hold, all in the hope of pleasing the awesome powers of nature and the celestial bodies they represent. So it should be remembered that, however beautiful some of the examples of astrological art may be, their purpose is mainly magico-religious. They are not works of art created for their own sake, in the modern sense. They are magical charms and diagrams.

Astrology is as old as mankind. No intelligent man at any time in prehistory or history could have looked up at the night sky and failed to notice the countless shining bodies and wonder with awe and amazement at their meaning and purpose. Long before man built cities, developed agriculture and writing, he studied the heavenly bodies and tried to relate their movements to his daily life on earth. Though no written records survive, prehistoric megalithic monuments and stone observatories such as those at Stonehenge in Britain and Carnac in Brittany (France) are ample evidence to show that early man throughout the ancient world had a reasonable and accurate knowledge of the heavens.

In India also, the early origins of astrology lie buried in unrecorded prehistory. Traditional histories, the puranas, give only mythological origins of astrology. They say that astrology originated among the gods. Brahma, the cosmic creator, was the first to propagate astrology. He taught the ‘science of the luminous bodies’ (jyotisa sastra) to Surya, the sun god. From Surya, the knowledge was passed down, generation after generation, through a line of divine and semi-divine teachers, to Bhrgu (or Garga, according to the Visnu Purana) the first human being to learn astrology. From Bhrgu onwards, astrology became the common heritage of all mankind.

Bhrgu is said to have been a great sage, an accomplished scholar and seer. His knowledge of astrology as well as his psychic powers were so highly developed that he cast horoscopes for all mankind-past, present and future. His horoscopes were preserved in a cryptic text called the Bhrgu Samhitu, but his key to the text was lost. A work of this title still exists, but whether it is the original text of Bhrgu or not, and whether anyone has the correct key or not, is difficult to say.

The Indus Valley civilisation in north-west India was the first to reach a high degree of sophistication in culture and religion. This civilisation thrived in many small city-states from about 3000 B.C. to 1500 B.C. During this period, archaeologists tell us, the cities were ruled by a kind of religious oligarchy of priest-kings. Many elements of present—day Hinduism—especially Tantra and Yoga—were evolved by the people of the Indus Valley civilisation. And it would, therefore, be reasonable to assume that they also studied the stars and the planets and evolved a sophisticated system of astrology and astronomy. But unfortunately, no written records survive to tell us anything about the astrological knowledge of the Indus Valley people.

The earliest definite and written record of a systematic study of the heavens comes from the Vedas. They were compiled over many centuries, from about 1500 B.C. to 600 B.C., and give us a picture of the development of astrologica1 astronomical ideas over a long period.

According to the Vedic hymns, the universe was divided into three realms: the earth (bhuh), the atmosphere (bhuvah) and the shining heavens (svah). The sun, the moon, the planets and the stars were in the shining heavens. The birds, the clouds and the demi—gods (gandharvas) lived and moved around in the realm of the atmosphere. Man, animals and plants lived on earth.

The sun was known to influence the seasons. There are frequent references in the Vedas to the solar year of 360 days, divided into 12 months of 30 days each, with five seasons.

|

ILLSUTRATIONS

|

9 | |

|

CHAPTER TWO : TIME AND SPACE

|

11 | |

| CHAPTER TWO : TIME AND SPACE | 35 | |

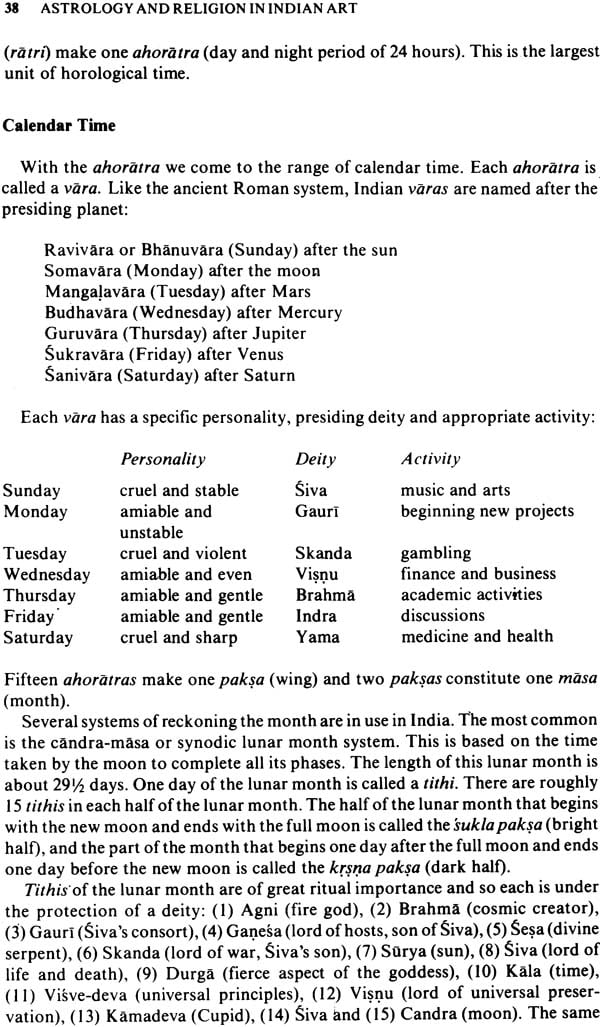

| Horological Time | 37 | |

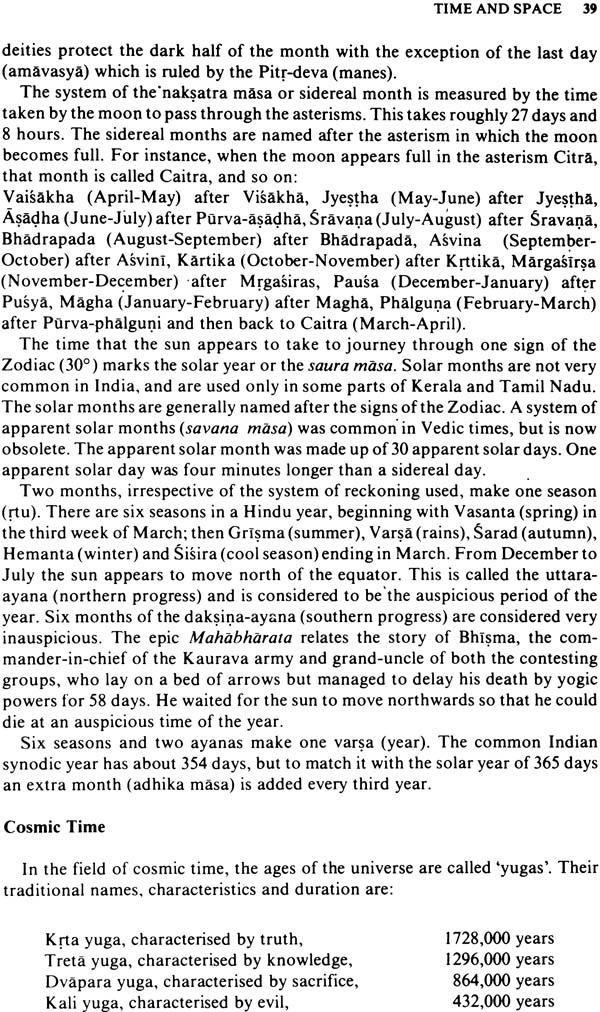

| Calendar Time | 38 | |

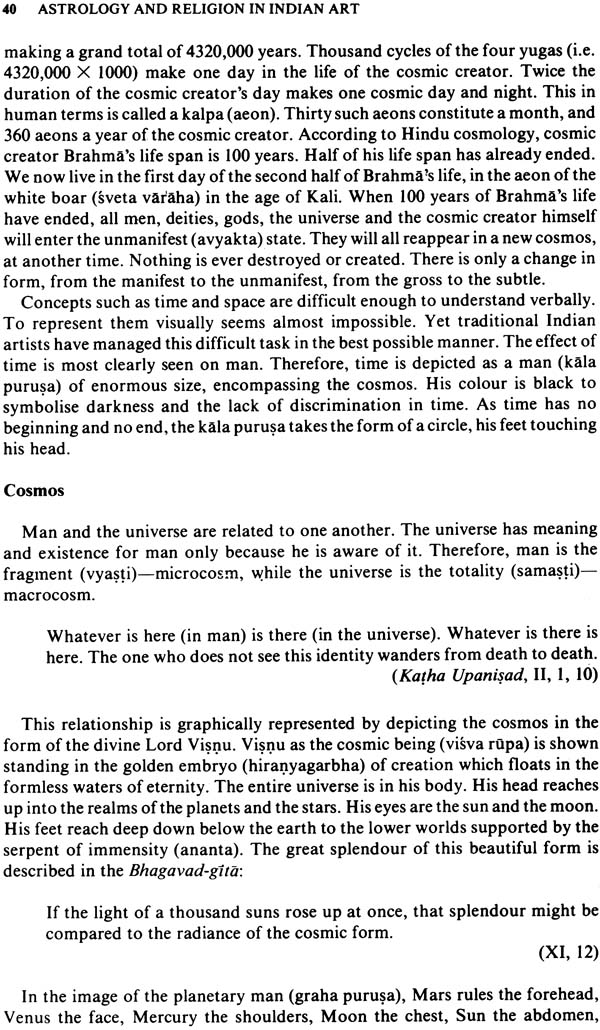

| Cosmic Time | 39 | |

| Cosmos | 40 | |

|

Realms of Existence

|

41 | |

| CHAPTER THREE : STARS AND PLANETS | 55 | |

| Mansions of the Moon (Naksatras) | 57 | |

| Planets | 62 | |

| The Sun (Surya) | 63 | |

| The Moon (Candra) | 68 | |

| Mars (Mangala) | 71 | |

| Mercury (Budha) | 72 | |

| Jupiter (Brhaspati) | 72 | |

| Venus (Sukra) | 73 | |

| Saturn (Saniscara) | 73 | |

|

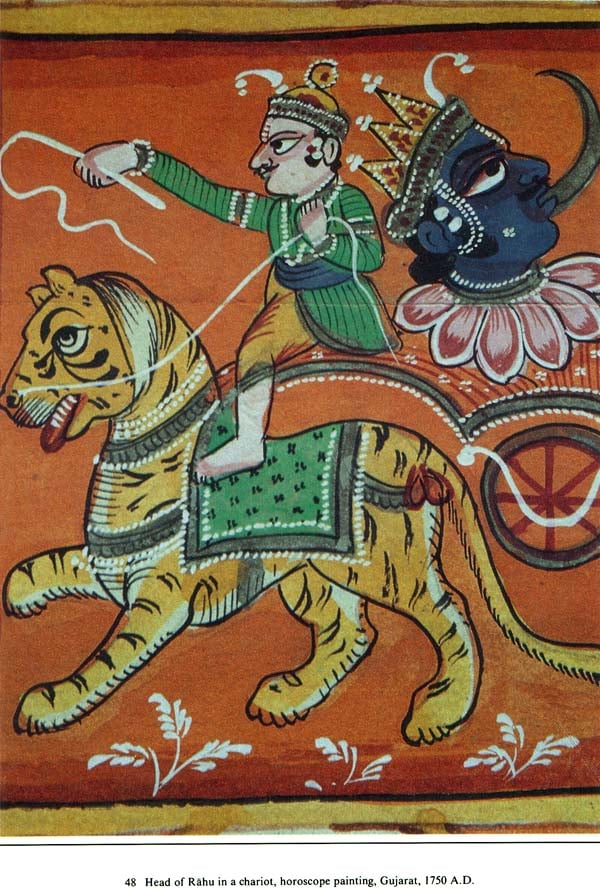

Rahu and Ketu (Ascending and Descending Nodes of the Moon)

|

75 | |

| CHAPTER FOUR : THE SIGNS OF THE ZODIAC | ||

|

The Zodiac (Rasi)

|

89 | |

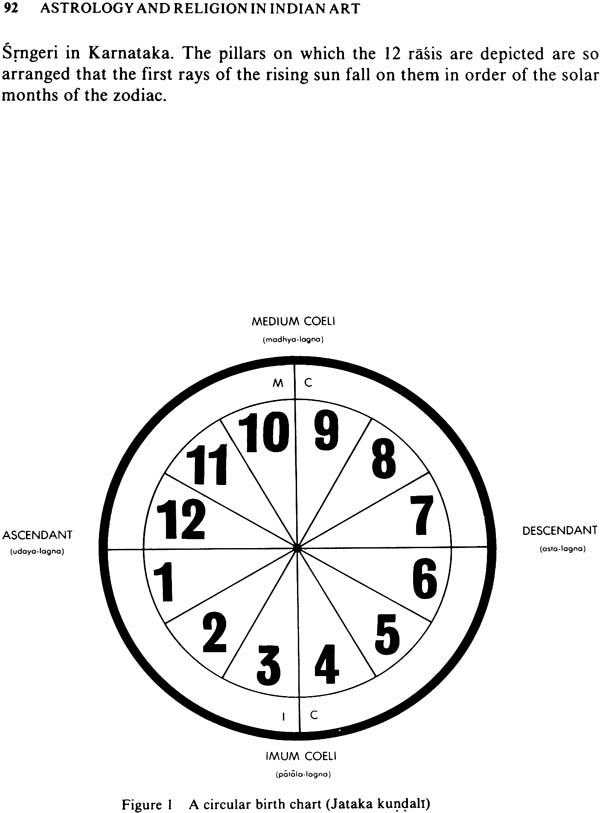

| CHAPTER FIVE : A PLAN OF THE HEAVENS | 105 | |

| Horoscope (Jataka-kundali) | 107 | |

| Aspects (Drsti) | 111 | |

| Divisions of the Horoscope | 111 | |

|

The Icon of Astrology (Jyotisa-Sastra-Svarupa)

|

113 | |

| CHAPTER SIX : WORSHIP | 123 | |

| Planetary Rites (Graha-Puja) | 125 | |

| Worship of the Sun | 125 | |

| Worship of the Moon | 127 | |

| Worship of the Planets | 129 | |

| Mangala (Mars | 129 | |

| Budha (Mercury) | 130 | |

| Brhaspati (Jupiter) | 130 | |

| Sukra (Venus) | 130 | |

| Sani (Saturn) | 131 | |

| Rahu and Ketu (the Nodes of the Moon) | 131 | |

|

Worship of Naksatras

|

135 | |

|

BIBLIOGRAPHY

|

145 | |

| INDEX | 147 | |

Send as free online greeting card

Visual Search